Jan 28, 2026

How are LLMs and AI Agents challenging marketplaces?

Marketplace investors increasingly fear three things. First, that GenAI-powered search and agents disintermediate classifieds at discovery, where intent is formed. Second, large horizontal platforms such as OpenAI or Google own the user relationship and redirect traffic, weakening brand-driven direct visits. Third, if discovery becomes a commodity, the long-term pricing power of classifieds most likely erodes. This fear has led to a broad de-rating across leading classifieds, despite limited evidence of traffic or revenue disruption so far.

To help understand whether this reaction might be justified, we examine below what LLMs actually do today, and how the buyer experience is likely to evolve in an agentic commerce world.

What are LLMs doing today?

Discovery starts with conversation

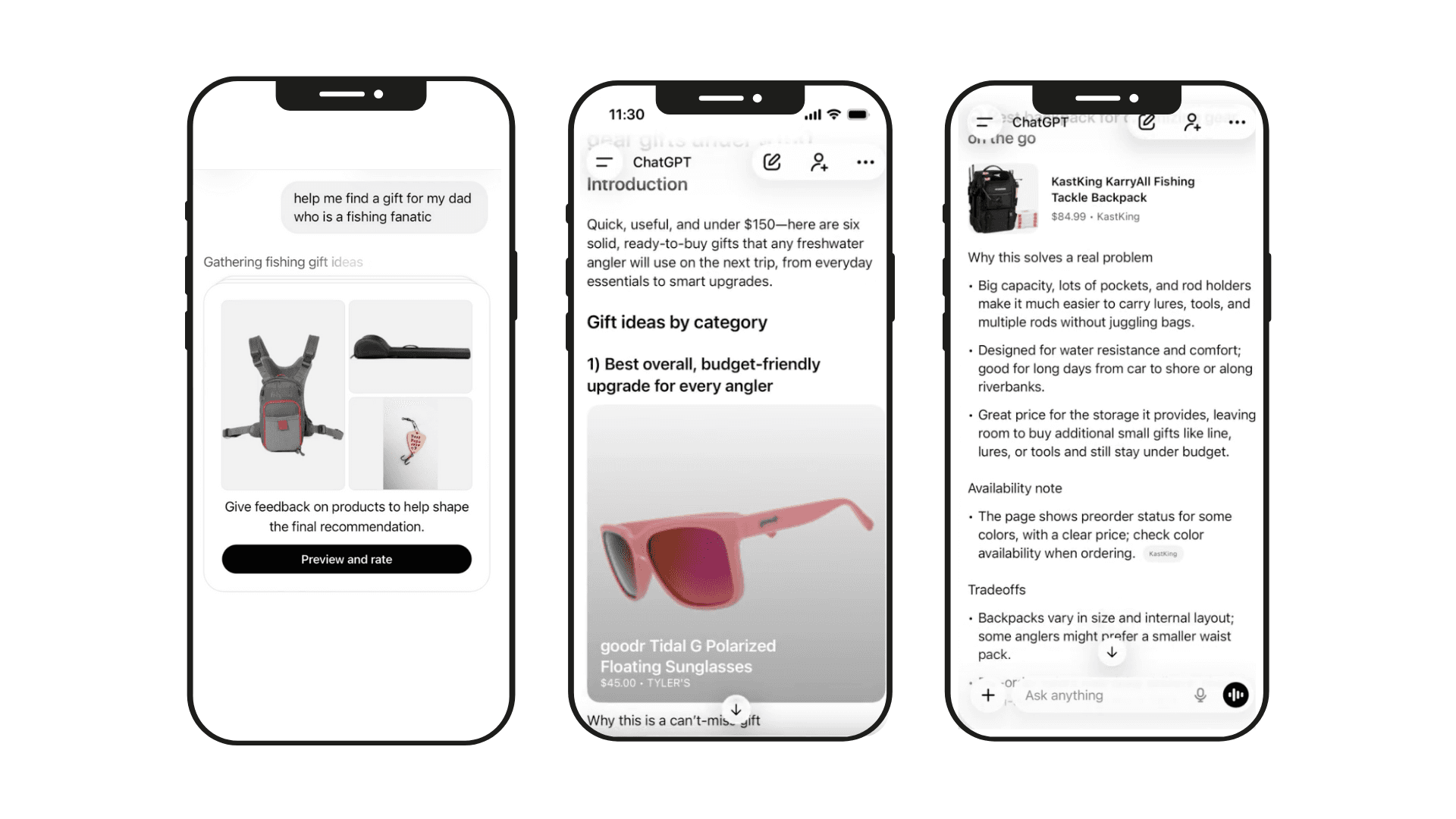

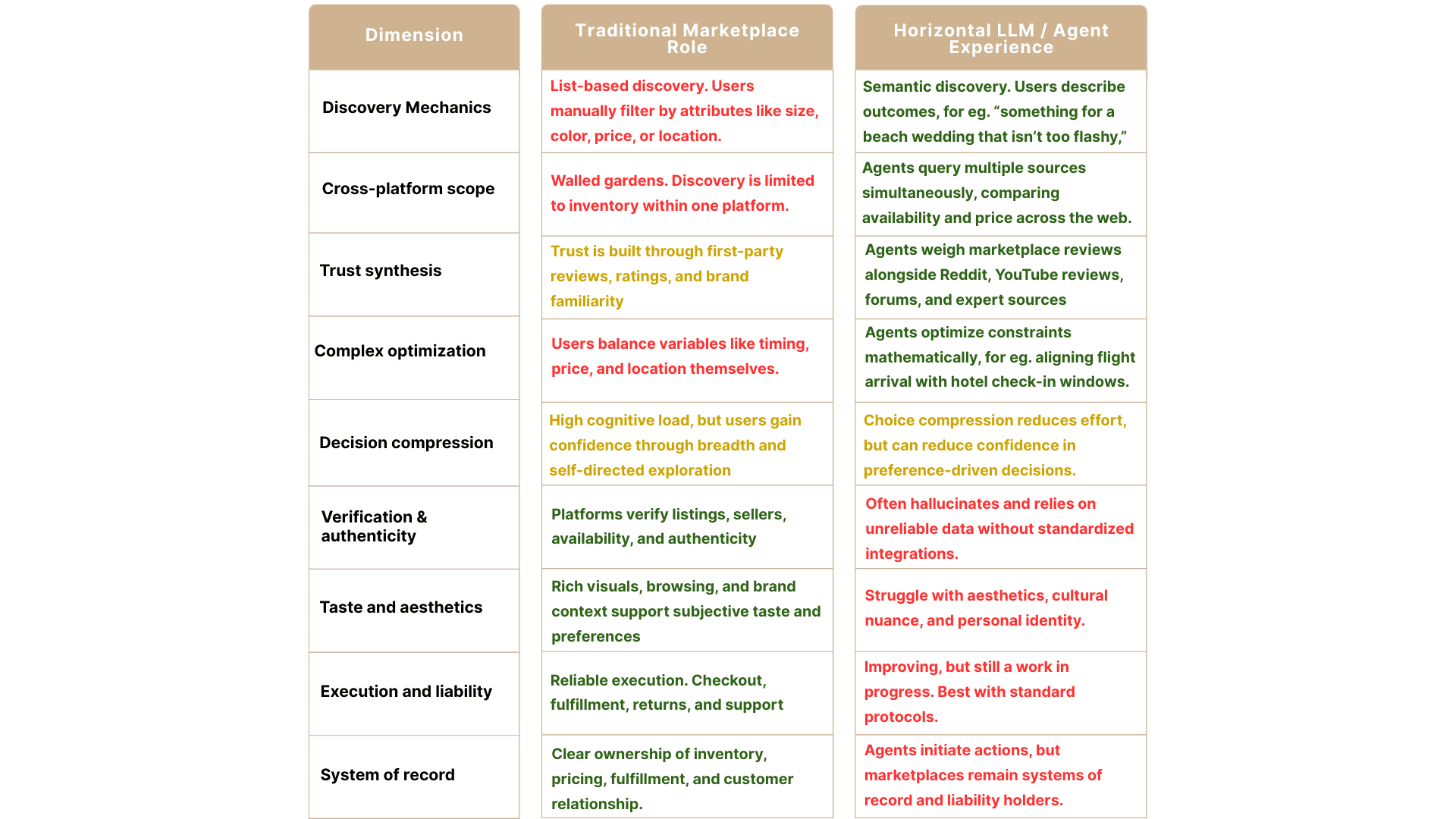

For a growing share of users, shopping begins with a prompt, not a search bar. Queries like “best running shoes under $100,” “gifts for a ceramics lover,” or “which air purifier is good for a small apartment” increasingly happen inside an LLM.

Instead of returning a ranked list of blue links, the model synthesises options across the web, surfaces a small set of relevant products, and explains trade-offs in plain language. The user no longer filters manually, the LLM does that work upfront.

Comparison without context switching

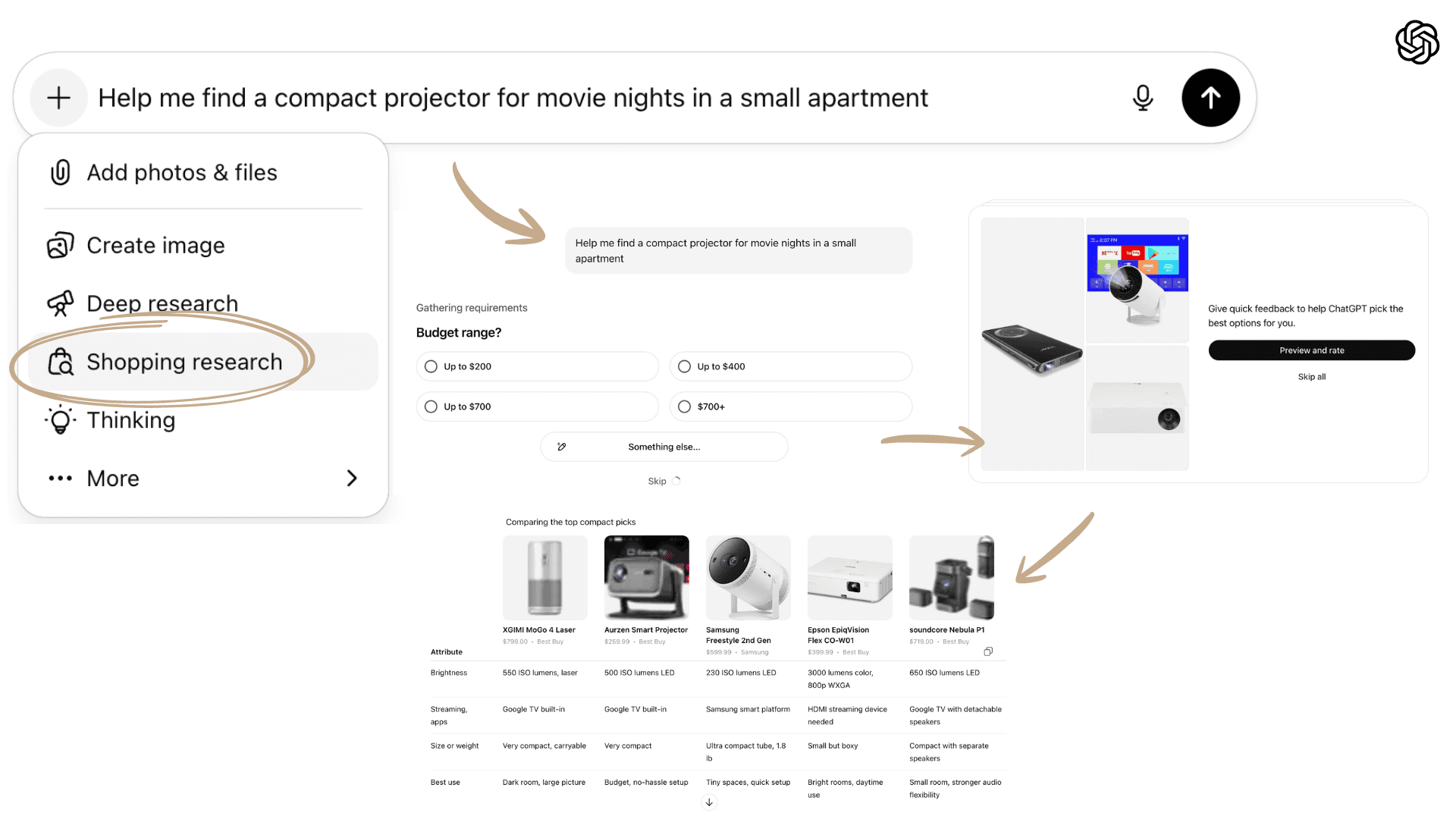

Shopping Research does more than show product names. It can synthesise and summarise key attributes side by side: performance, features, user satisfaction, quality trade-offs, and price. Users can refine results in a conversation, without juggling multiple tabs or fragmented search results.

Guided, personalised recommendations

The model uses your inputs and memory where enabled in settings; priorities like budget, preferred brands, and past preferences, to tailor results. This moves the interface from generic listings toward customized guides more like a personal shopper than a search engine.

Commerce still flows outward

In the current phase, users typically still complete purchases by clicking through to merchant sites. The LLM does the heavy lifting in research and comparison, pulling scattered information into an organized, context-rich view.

Early forms of “in-interface” commerce

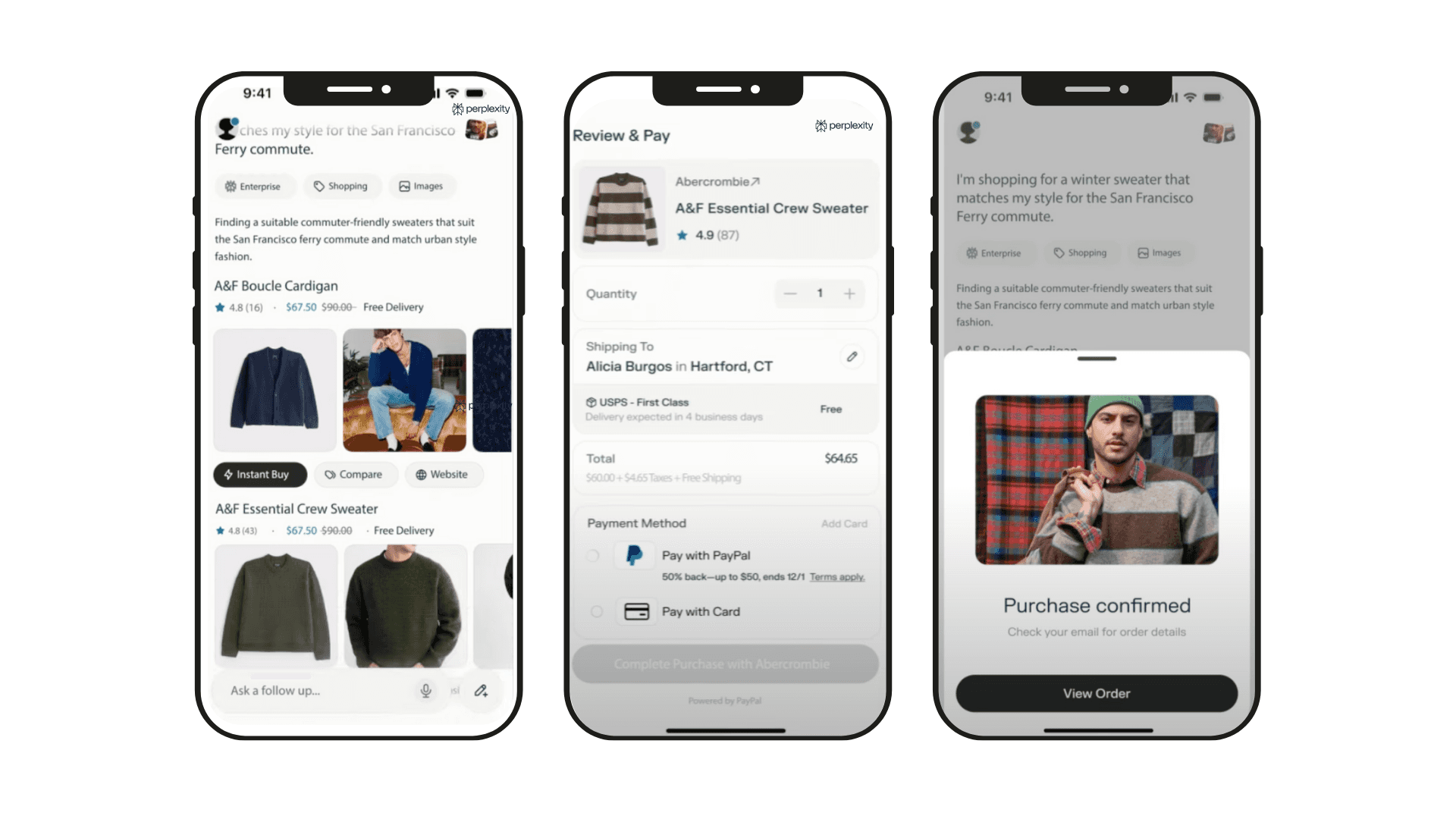

Some LLMs have begun to layer lightweight commerce into this experience. Features like Perplexity’s in-chat purchases or early checkout flows inside ChatGPT, allow users to move from discovery to purchase with minimal friction.

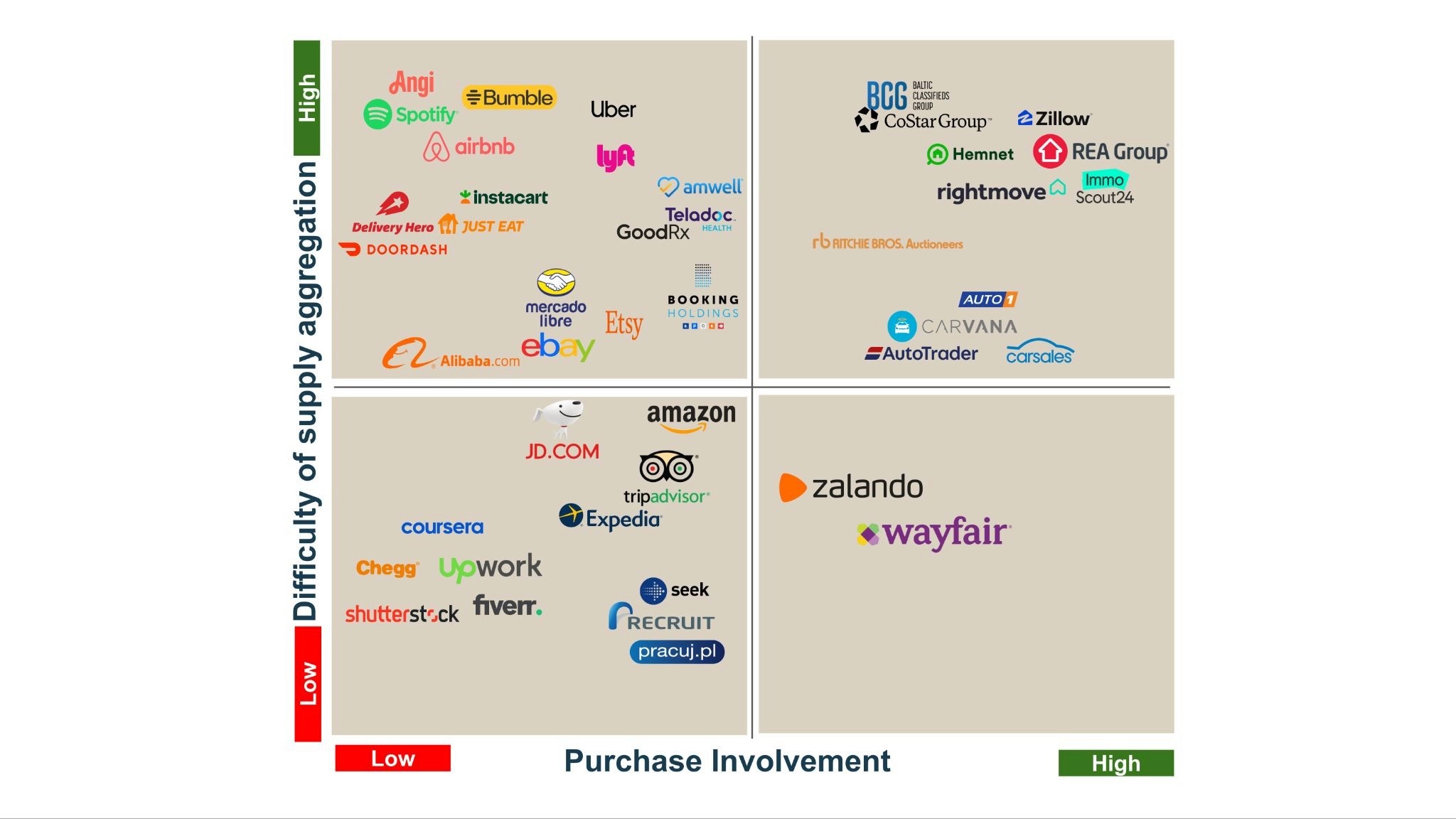

Right now, LLMs seem to be moving away from pure search engines and edging closer to shopping interfaces. But this only goes so far. As we outlined in our purchase involvement matrix last week, agent-led execution works best in low to mid-involvement categories -repeatable, spec-driven purchases with limited downside. As involvement rises, delegation starts to break down. Agents remain valuable for research and comparison, but execution still happens elsewhere.

What happens when we move from deciding what to buy to consummating the transaction?

When LLMs become agents: instant checkout, MCP, and ACP

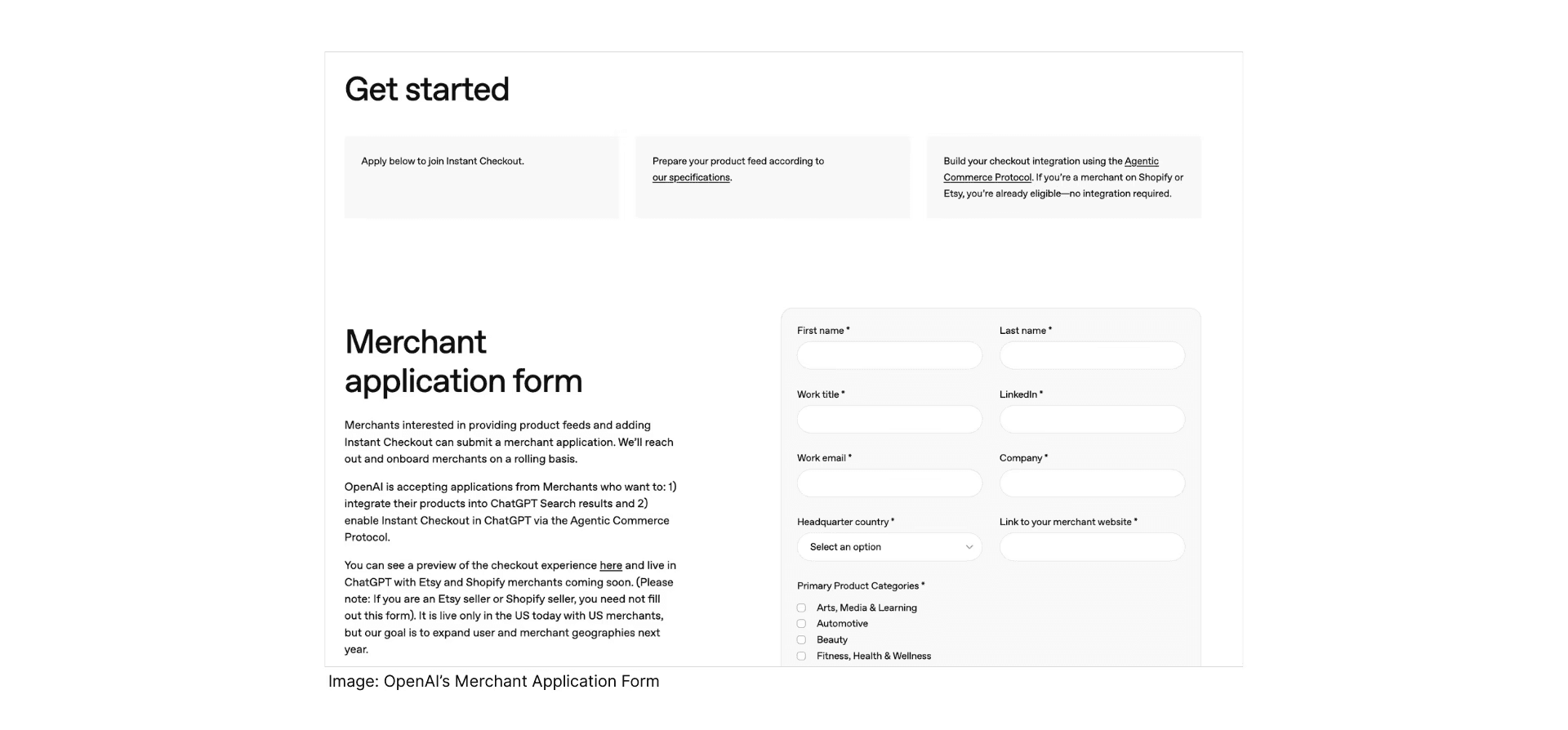

The shift from assistance to execution happens when standardized protocols sit beneath the interface. OpenAI’s Instant Checkout in ChatGPT, powered by the Agentic Commerce Protocol and built with Stripe, is the clearest signal of how this evolves.

Agentic Commerce Protocol (ACP) defines how an AI agent securely passes order, payment, and fulfilment details to a merchant. The merchant remains the merchant of record, controls pricing, fulfilment, returns, and customer support, while the AI acts as the delegated interface.

Shared payment tokens, developed with Stripe, ensure that payment credentials are scoped to a specific merchant and amount. The agent never holds raw card data, reducing fraud and liability.

For the user, the result feels like a closed loop. Discovery, decision, and checkout happen in one place. For merchants and marketplaces, the interface shifts upward while systems of record remain unchanged.

This is the inflection point markets might be reacting to. Once MCP-like data access and ACP-like transaction standards mature, horizontal LLMs no longer just recommend where to go. They become where commerce happens.

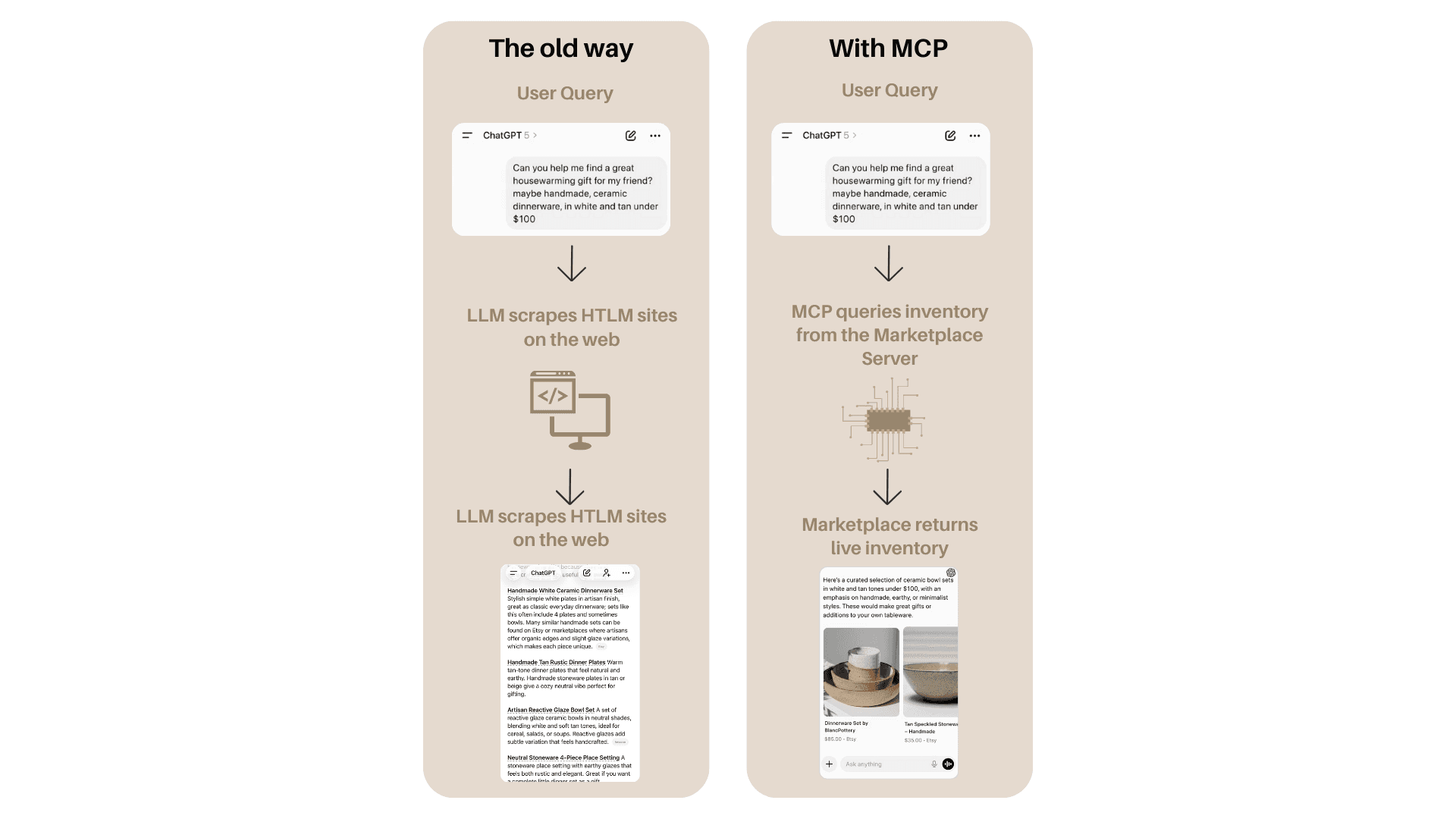

Standard LLMs are frozen in time; they cannot access real-time inventory or pricing. Scraping HTML is brittle, resource-intensive, and often blocked by anti-bot defenses.

MCP allows a marketplace (the Server) to expose proprietary data, such as live inventory, shipping tables, dynamic pricing, directly to an AI agent (the Client) via a standardized API.

What Agents are doing beyond LLMs

AI agents represent the moment where horizontal LLMs move from being an interface to becoming the operating layer. Instead of pointing users to destinations, systems like ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, or Perplexity increasingly aim to complete tasks end to end without the user ever leaving the conversational interface. Some concrete examples of how this is playing out in real time:

In-interface purchasing: A user asks the agent to “find me a suitable commuter friendly sweater.” The agent surfaces a few options across marketplaces, explains differences in material, fit, brand, and care, confirms sizing and color preferences, and completes payment directly within the chat. Order confirmation and tracking appear in-interface. The user never opens a marketplace app, a browser tab, or a checkout page. The user never opens a marketplace app, a browser tab, or a checkout page, the entire transaction happens inside the conversational layer.

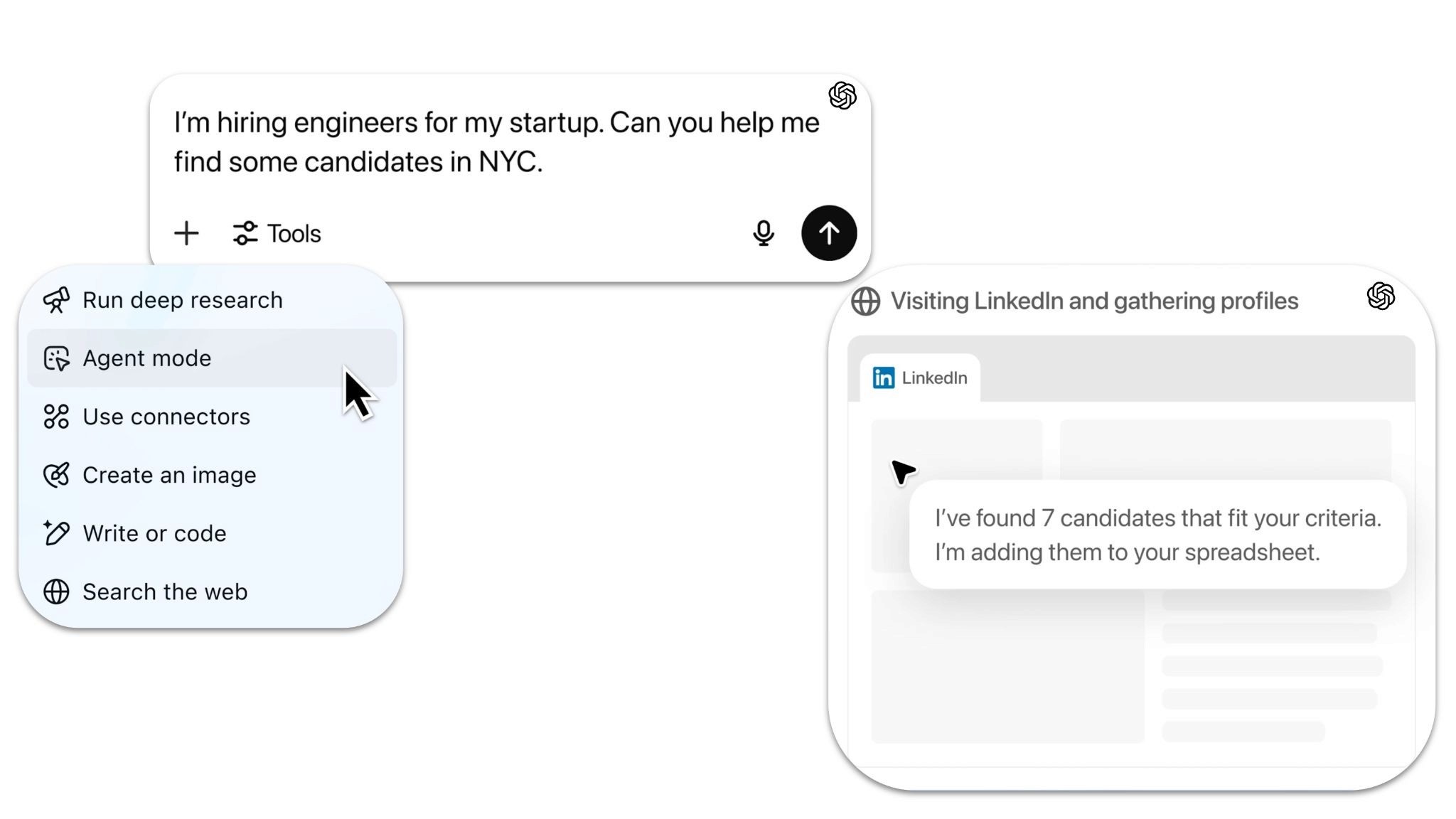

Hiring and Talent Sourcing: A founder asks the agent to “hire a senior backend engineer for my NYC startup.” The agent converts intent into constraints (location, seniority, stack, prior experience), navigates professional networks directly, reviews profiles and work histories, and filters candidates accordingly. It presents a short shortlist for review, with outreach or follow-up still executed via the underlying platform.

Cross-marketplace sourcing: A user asks the agent to “find a two-bedroom apartment to rent in Brooklyn under $4,000, close to the subway.” The agent queries multiple real estate platforms, applies constraints on price, location, commute time, and availability, and returns a short list of relevant listings with summarized trade-offs. The actual inquiry and transaction still occur on the underlying property portals or with brokers, but discovery and filtering are potentially, at least in part, agent-owned.

Below are some near-term, practical use cases that show how agent-led capabilities might begin to surface in day-to-day use cases:

Replenishment and repeat purchases: A user tells the agent, “Make sure I never run out of dog food.” The agent tracks prior purchases, preferred brands, delivery cadence, and price sensitivity. When inventory is likely running low, it autonomously reorders within a predefined budget, confirms the order in-chat, and surfaces the receipt. The user never opens Amazon or Instacart.

Price monitoring and deal execution: A user asks the agent to “buy these Sony headphones if the price drops below $250.” The agent monitors prices across retailers, alerts the user when conditions are met, and executes the purchase upon confirmation, all inside the chat interface.

Travel bookings: A user asks the agent to plan a three-day work trip to London. The agent proposes flight options, hotels near the office, and ground transport, explaining trade-offs. Once the user approves, bookings are executed via partner APIs, with confirmations returned directly in-chat.

The reality - why we aren’t there yet

Despite the promise, we are not yet in a "Zero-Click" economy. As we stand today, the systems are intelligent enough to understand intent, but too fragile to execute reliably.

The involvement spectrum

Low involvement (commodities): High Agent Adoption. For dishwasher tabs or batteries, consumers are happy to delegate. "Just buy the usual." The risk of error is low ($15 loss).

High involvement (experience/ identity): Low Agent Adoption. Homes, cars, education, medical services, or meaningful travel decisions require trust, verification, and emotional confidence. Here, speed is less valuable than reassurance. Users want to see, compare, pause, and feel in control.

Visual blindness: Current agents treat shopping as a text problem, it’s a multimodal judgment problem, where visuals, context, cultural cues, and personal identity all interact in ways that are hard to reduce to text or specs alone. If you ask an agent for "mid-century modern chairs," it relies on metadata tags that are often spammy or inaccurate. It cannot "judge" aesthetics the way a human eye scanning a Pinterest feed can.

The trust deficit: A user may rely on an agent to research a used car, compare prices, filter by mileage and year, surface common issues, and shortlist options across platforms. But the final decision rarely happens autonomously. Verification still shifts to a trusted interface, where users review detailed photos, service history, inspection reports, and often speak to a dealer or arrange a test drive before committing.

Structural limits of agent-led discovery

Bias and partial visibility: Agent-led discovery favours supply that is machine-legible and API-accessible. Sellers with structured data and direct integrations surface more easily, while long-tail, unstructured, or visually differentiated supply risks being excluded regardless of quality. Unlike marketplaces, where ranking logic is explicit, agent-driven selection is often opaque. Users cannot easily see what was excluded or why. This creates a perception risk: even accurate recommendations may feel incomplete, commercially influenced, or strategically filtered rather than exhaustive.

Choice compression vs confidence trade-off: By narrowing options, agents reduce cognitive load but can also reduce confidence in categories with subjective preferences. Users often value breadth as reassurance that they have seen enough of the market. In these cases, a short, optimised list can feel constraining, increasing suspicion that better alternatives exist outside the agent’s view. Choice compression works best where preferences are stable and outcomes are standardised; it breaks down where taste, identity, or exploration matter.

Hallucinations in commerce

Product fabrication: Agents have been documented inventing product features to satisfy a user's prompt. In commerce, a hallucination is a financial liability. Agents have been documented inventing return policies (e.g., the Air Canada chatbot case) or fabricating product features (claiming a stroller is "airline approved" when it isn't)

Phantom inventory: Agents may claim an item is in stock based on outdated scrape data, only for the user to find it sold out upon click-through. This "Inventory Phantom" phenomenon damages trust and increases cart abandonment. The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is trying to solve this, but adoption is early.

The trust deficit

Consumer hesitation: In a Bain Survey, 72% of consumers claimed using AI for research, only roughly 24% feel comfortable letting an AI execute a financial transaction on their behalf. Trust drops significantly for high-stakes purchases. This mirrors early e-commerce adoption; consumers hesitated to shop online or store card details due to trust and security concerns. Over time, better UX, safeguards, and repeated successful transactions normalised the behavior.

Strategic defences adopted by marketplaces

Crawler blocking: Retailers like Amazon have blocked AI agent crawlers, rendering roughly 40% of U.S. e-commerce "invisible" to the agent’s direct scraping mechanisms. This forces agents to rely on third-party sources like Reddit for product information, paradoxically lowering the quality of data available to the agent.

Login gates: By moving price, inventory, and rich descriptions behind login walls, marketplaces ensure that anonymous agents cannot scrape valuable data. This strategy forces agents to "authenticate" (via protocols like ACP) or fail, giving the marketplace leverage to demand revenue-sharing agreements.

Anti-bot defences: Companies like Cloudflare are selling "AI-fighter" modes that distinguish between a human browser and an agentic browser, allowing marketplaces to selectively block high-volume API calls from agents that do not pay for access. This technical arms race is making agentic data retrieval increasingly difficult and expensive.

Agent strengths vs. marketplace limitations

LLMs as would-be marketplaces

It’s also worth noting that LLMs are not just acting as intermediaries, they are increasingly positioning themselves as marketplaces. OpenAI’s Instant Checkout and merchant onboarding flow makes this explicit: suppliers are encouraged to integrate directly, expose product feeds, and transact inside the conversational interface.

This works well where supply is already structured and standardized. The challenge emerges in categories where supply is fragmented, heterogeneous, and harder to normalize. Used cars, homes, local services, and many experience-driven purchases require more than listings and prices. They rely on rich context, inspection, visuals, reputation, and repeated trust-building. These are the categories where marketplaces have spent years aggregating supply, standardizing quality, and making the market legible.

Should marketplaces be worried?

The recent de-rating of public classifieds reflects a concern that control of discovery is shifting from marketplaces to horizontal LLM interfaces. That concern is directionally correct, but incomplete.

We are currently seeing a divergence in how this technology is being deployed, leading to two contradictory futures for the marketplace user experience.

Future A: the "Super-Google" (meta-aggregation)

In this scenario, LLMs remain a "Discovery Layer." They act as a hyper-efficient portal that summarizes options but ultimately sends traffic downstream to the existing marketplaces (Amazon, Airbnb) for the transaction.

Future B: the "Invisible Hand"

In this scenario, agents become the browser and the buyer. They negotiate, book, and pay via API. The traditional marketplace interface becomes obsolete "plumbing."

In our opinion, we are not there yet. We are in a messy transition phase where the "Search" is better than Google, but the "Buy" is not a match for Amazon. Many agents are brilliant at retrieval (finding a needle in a haystack) but mediocre at judgment (knowing if the needle fits the user’s taste and preference). Until agents can reliably handle the nuance of "taste" and the liability of "transaction," the journey will remain hybrid.

LLMs are increasingly shaping intent formation. Discovery is becoming conversational, cross-platform, and less tied to any single marketplace interface, weakening direct traffic as a standalone moat. In that sense, the market reaction reflects a real structural shift.

However, discovery alone does not determine value capture. Execution, trust, verification, and liability remain anchored to marketplaces, particularly for high-involvement purchases. Agents accelerate research and comparison, but do not yet replace systems of record.

The outcome is therefore not uniform. Low-involvement, repeatable transactions are increasingly delegable to agents. High-involvement decisions continue to rely on marketplace infrastructure, with agents acting as a pre-transaction layer rather than a substitute.

This points to a hybrid equilibrium: discovery fragments upward, while transaction integrity and trust remain downstream. The current de-rating prices in the former more aggressively than the latter.

In Part 3, we will explore the AI-Native marketplaces, the new startup marketplaces that are building specifically for this agent-led world.